Sunday, January 28, 2018

How a Misfit Group of Computer Geeks and English Majors Transformed Wall Street

The New York Magazine, 18-Jan-18

By Michelle Celarier

In the summer of 1988, the hedge-fund manager Donald Sussman took a call from a former Columbia University computer-science professor wanting advice on his new Wall Street career.

“I’d like to come see you,” David Shaw, then 37 years old, told Sussman. Shaw had grown up in California, receiving a Ph.D. at Stanford University, then moved to New York to teach at Columbia before joining investment bank Morgan Stanley, which had a new secretive trading group that was using computer modeling. A neophyte in the ways of Wall Street, Shaw wanted Sussman, who founded the investment firm Paloma Partners, to look at an offer he had received from Morgan Stanley’s rival, Goldman Sachs.

Sussman’s career has been built on recognizing and financing hedge-fund talent, but he had never encountered anyone like David Shaw. The cerebral computer scientist would go on to become a pioneer in a revolution in finance that would computerize the industry, turn long-standing practices on their head, and replace a culture of tough-guy traders with brainy eccentrics — not just math and science geeks, but musicians and writers — wearing jeans and T-shirts.

A harbinger of the techies who would storm Wall Street in a decade, this new generation of hedge-fund introverts would replace the profanity-laced trading rooms of the 1980s with quiet libraries of algorithmic research in every corner of the markets. They would also launch an early email system and look into the prospect of online retailing, leading one of Shaw’s most ambitious employees to take the idea and run with it. Yes, the seeds of Jeff Bezos’s Amazon were planted at a New York City hedge fund.

Thirty years ago, all of that was yet to come. All Shaw told Sussman at the time was, “I think I can use technology to trade securities.”

Sussman told Shaw the Goldman offer he had received was inadequate. “If you’re confident this idea is going to work, you should come work for me,” Sussman told Shaw. The offer led to three days of sailing in Long Island Sound on Sussman’s 45-foot sloop with the financier, Shaw, and his partner, Peter Laventhol. The two men —without disclosing many details — “convinced me they believed they could generate models that would identify portfolios that would be market-neutral and able to outperform others,” Sussman remembers. In lay terms, the strategy would make a lot of money without taking much risk.

Hedge funds were still fairly primitive, and while they were already using mathematical formulas to capture small price disparities in such esoteric instruments as convertible bonds — then a dominant hedge-fund strategy — Shaw was planning to take the math to a whole new level.

Paloma Partners agreed to invest $30 million with D.E. Shaw. Since then, the company has grown into an estimated $47 billion firm, earning its investors more than $25 billion — as of the end of 2016, tied for the third biggest haul ever. It has made millionaires out of scores of employees and a multibillionaire out of Shaw, who stepped back in 2001 from day-to-day operation of the firm to start D.E. Shaw Research, which conducts computational biochemistry research in an effort to help cure cancer and other diseases. Shaw is estimated by Forbes to be worth $5.5 billion, and remains as elusive as ever: He declined to speak to New York for this article.

Meanwhile, the quantitative revolution D.E. Shaw helped spawn has become the biggest trend in hedge funds today, capturing some $500 billion of the industry’s more than $3 trillion in assets and dominating the top tier. Seven out of the top ten largest funds are considered “quants,” including D.E. Shaw itself. One of those seven quants, Two Sigma, was started by D.E. Shaw veterans. But the changes D.E. Shaw wrought haven’t just been felt in hedge funds. Shaw spit out orders accounting for an estimated 2 percent of the trading volume of the New York Stock Exchange in its early years, and thanks to it and other emerging quants, the NYSE was forced to automate. By the end of the 1990s, electronic stock exchanges were driving trading prices down, and by 2001, stocks began to be traded in penny increments, instead of eighths. These changes made it cheaper and easier for all investors to get into the game, leading to an explosion in trading volume.

From the beginning, D.E. Shaw was a quirky enterprise, even for a hedge fund. The first office was far from Wall Street, in a loftlike space above Revolution Books, a communist bookstore on 16th Street, in what was then a still fairly seedy Union Square. The office, about 1,200 square feet, was bare, with freshly painted walls and a tin ceiling. But it boasted two Sun Microsystem computers — the fastest, most sophisticated computers then in vogue on Wall Street. “He needed Ferraris; we bought him Ferraris,” says Sussman.

As Shaw sought to build his newfangled firm, he didn’t want to hire people steeped in Wall Street’s ways. Likewise, those who joined D.E. Shaw typically disdained the notion of working on the Street. “I thought to myself, No way,” says Lou Salkind, remembering a call he received from Shaw in the summer of 1988 asking him if he would be interested in joining his start-up. Salkind was finishing his Ph.D. in computer science at New York University and on the hunt for a job, but Wall Street turned him off. “The year before, I’d been recruited by a few firms on Wall Street. I was skeptical I would like anything in finance.”

Lacking any other job offers, he agreed to meet with Shaw. After all, his hedge fund’s office was about ten blocks away from NYU. The two men went to lunch at nearby Union Square Cafe, where they got to talking about gambling, one of Salkind’s passions. Born in New York City, Salkind had learned to count cards at an early age and developed a horse-betting system at age 13. He had no idea such mathematical skills would come in handy at a hedge fund. “I had a blast,” he recalls.

When they returned to the office, Shaw began laying out his vision. “What I want to build here is a company at the intersection of technology and finance,” he told Salkind. As with Sussman, Shaw wouldn’t tell Salkind much more than that, but he did speculate that his firm might be able to replace Wall Street market makers: “They prepare to buy at the bid, hold, and sell at a higher price. The difference is what you try to capture. We could do a lot of this stuff automatically with computers,” he told the fellow computer scientist.

“Oh, you’re like a bookie. That’s the vig,” said Salkind, who was immediately sold on the job. Salkind, who retired in 2014, became one of the first employees of D.E. Shaw.

In the hedge fund’s early days, Sussman would visit the office weekly. “Once they started trading, they started making money out of the box,” he remembers. “These were very serious folks. I used to go and sit next to them watching them trade. They didn’t miss a goddamn thing,” he recalls. “The atmosphere of the place was unlike any other investment firm. It was like going into the research room in the Library of Congress.”

In 1990, Anne Dinning, another NYU computer-science Ph.D. who knew Salkind from his days there, struck up a conversation with Shaw at a party at Salkind’s home. “I didn’t even know what a hedge fund was,” she recalls, but agreed to interview for a job at Shaw “as a lark,” and ended up joining, despite her initial desire to become an academic.

“My first job was to work on some forecast of Japanese equities,” she says. Dinning didn’t have to know anything about the companies or the Japanese stock market. The computer would figure it all out. In the early days, she would run 24-hour simulations, waking up every six hours in the night to check on their progress. Once the algorithms were ready for live trading, “I’d look at the P&L every day and see if it’s doing what I thought it would. It was like an experiment. And I could see the immediate results,” says Dinning. As the firm expanded, Dinning ended up running both the London and Tokyo offices of D.E. Shaw, and both she and Salkind became members of an unorthodox six-person executive committee that ran the firm in a surprisingly effective consensus manner after Shaw stepped back from its day-to-day management. (He is still involved in strategic decisions.)

While D.E. Shaw was minting money, David Shaw’s vision didn’t stop with creating a quantitative hedge fund. Technology, he knew, had the capacity to transform our everyday lives. As an academic, Shaw had already used the Arpanet, the precursor to the internet, to communicate with other scientists. That helped inspire one of the first free internet-based email systems, Juno. With equity capital from D.E. Shaw, the service launched in 1996, went public, and eventually merged with a competitor.

Free email was only one of Shaw’s early initiatives, explains Charles Ardai, who joined Shaw in 1991 with a degree in English (specifically, British Romantic poetry) from Columbia, one of the first of many unconventional hires who didn’t have a background in the hard sciences.

“He went to one of my co-workers and said, ‘I think people will buy things on the internet. They’re going to shop on the internet. What’s more, they’re not just going to shop.’ This, I swear to you, is what David said: ‘Not only will people shop, but when they buy something — let’s say they buy a pipe for watering their garden — they’re going to try a pipe, and they’re going to say, this pipe is good, or this pipe is bad, and they’re going to post reviews, and other people will see them and pick the right instead of the wrong pipe, because somebody else told them, I like this pipe. I don’t like that pipe.’”

Jeff Bezos, who had joined in 1990, was in charge of the online retailing project at D.E. Shaw. He became so enthused about the possibilities that he asked Shaw if he could take the idea and run with it on his own. Shaw agreed, and Amazon was soon born. (Shaw didn’t take a stake in the now-$620 billion company.)

Upon graduating from Columbia, Ardai says he had been so surprised to receive a letter from Shaw asking him to apply for a job that he thought “it must be a scam.” Soon after the 22-year-old joined, he was tasked with setting up Shaw’s recruiting department. “We’ve filled the company with everything from a chess master, to published writers, to stand-up comedians — people who really excel in one field or another — we had an Olympic-caliber fencer, and at one point we had a demolitions expert,” he says. One of D.E. Shaw’s best traders had tattoos all over his arms and couldn’t get hired anywhere on Wall Street. Another was a trombone player who eventually left to create a music program in the Bronx. (Ardai also has other interests; he is the founder and editor of Hard Case Crime, a line of pulp-style paperback crime novels.)

D.E. Shaw’s hiring process may have a far-flung reach, but by no means is it egalitarian. In fact, its recruiting letters once started with an assertion that the firm is “unapologetically elitist.” Once eyebrow-raising, the hedge fund’s hiring practices are no longer abnormal, as they have been adopted by giant tech firms like Google, and of course, Amazon, which even uses the same grading system as D.E. Shaw when interviewing candidates.

The casual dress code embraced by D.E. Shaw has also become de rigueur at tech giants. Though viewed as shocking in Shaw’s early years, such attire is also common at many New York hedge funds today. “One of the goals at D.E. Shaw has always been ‘let’s remove all of the unnecessary constraints,’ for example, why require people to wear neckties?” explains Ardai. The crew at D.E. Shaw was so disheveled that, according to Shaw lore, one disgusted white-shoe law firm moved out of a midtown office tower that the hedge fund occupied — in protest. These days, David Shaw, whose research project is housed across the street from the hedge fund, is often seen wearing a black T-shirt and cargo shorts — even in the middle of winter.

For all of its attempts at modesty, D.E. Shaw has come a ways from its years above a communist bookstore. With more than 1,000 employees, in 2010 the firm moved into new offices at 1166 Sixth Avenue (its fourth New York City home) whose austere reception area has a ceiling and walls covered with screens designed to look like computer punch cards.

In 2015, former Google executive chairman Eric Schmidt, a longtime investor in D.E. Shaw’s hedge funds, took a 20 percent stake in the firm, buying out bankrupt Lehman Brothers’ earlier investment. These days, there’s so much money chasing quants that the earlier strategy of betting on inefficiencies in public equity markets has become less profitable. Innovator D.E. Shaw has moved from its beginnings in equity arbitrage into other arenas like distressed debt and emerging markets, where it uses its quantitative techniques to help give it an edge while relying on humans, not computer models, to make trading decisions.

As the firm gets ready to celebrate its 30th anniversary, David Shaw has not disappointed his first investor, Donald Sussman, whose firm eventually had hundreds of millions of dollars invested with D.E. Shaw. “I never doubted him for a minute,” he says. “I never envisioned that D.E. Shaw would be $47 billion, but I did envision how David would change the world of finance.”

Monday, January 22, 2018

Wednesday, January 17, 2018

How a 22-Year-Old Discovered the Worst Chip Flaws in History

Bloomberg, 17-Jan-18

By Jeremy Kahn , Alex Webb , and Mara Bernath

In 2013, a teenager named Jann Horn attended a reception in Berlin hosted by Chancellor Angela Merkel. He and 64 other young Germans had done well in a government-run competition designed to encourage students to pursue scientific research.

In Horn’s case, it worked. Last summer, as a 22-year-old Google cybersecurity researcher, he was first to report the biggest chip vulnerabilities ever discovered. The industry is still reeling from his findings, and processors will be designed differently from now on. That’s made him a reluctant celebrity, evidenced by the rousing reception and eager questions he received at an industry conference in Zurich last week.

Interviews with Horn and people who know him show how a combination of dogged determination and a powerful mind helped him stumble upon features and flaws that have been around for over a decade but had gone undetected, leaving most personal computers, internet servers and smartphones exposed to potential hacking.

Other researchers who found the same security holes months after Horn are amazed he worked alone. "We were several teams, and we had clues where to start. He was working from scratch," said Daniel Gruss, part of a team at Graz University of Technology in Austria that later uncovered what are now known as Meltdown and Spectre.

Horn wasn’t looking to discover a major vulnerability in the world’s computer chips when, in late April, he began reading Intel Corp. processor manuals that are thousands of pages long. He said he simply wanted to make sure the computer hardware could handle a particularly intensive bit of number-crunching code he’d created.

But Zurich-based Horn works at Project Zero, an elite unit of Alphabet Inc.’s Google, made up of cybersleuths who hunt for "zero day" vulnerabilities, unintended design flaws that can be exploited by hackers to break into computer systems.

So he started looking closely at how chips handle speculative execution -- a speed-enhancing technique where the processor tries to guess what part of code it will be required to execute next and starts performing those steps ahead of time -- and fetching the required data. Horn said the manuals stated that if the processor guessed wrong, the data from those misguided forays would still be stored in the chip’s memory. Horn realized that, once there, the information might be exposed by a clever hacker.

"At this point, I realized that the code pattern we were working on might potentially leak secret data," Horn said in emailed responses to Bloomberg questions. "I then realized that this could -- at least in theory -- affect more than just the code snippet we were working on."

That started what he called a "gradual process" of further investigation that led to the vulnerabilities. Horn said he was aware of other research, including from Gruss and the team at Graz, on how tiny differences in the time it takes a processor to retrieve information could let attackers learn where information is stored.

Horn discussed this with another young researcher at Google in Zurich, Felix Wilhelm, who pointed Horn to similar research he and others had done. This led Horn to what he called "a big aha moment." The techniques Wilhelm and others were testing could be "inverted" to force the processor to run new speculative executions that it wouldn’t ordinarily try. This would trick the chip into retrieving specific data that could be accessed by hackers.

Having come across these ways to attack chips, Horn said he consulted with Robert Swiecki, an older Google colleague whose computer he had borrowed to test some of his ideas. Swiecki advised him how best to tell Intel, ARM Holdings Plc. and Advanced Micro Devices Inc. about the flaws, which Horn did on June 1.

That set off a scramble by the world’s largest technology companies to patch the security holes. By early January, when Meltdown and Spectre were announced to the world, most of the credit went to Horn. The official online hub for descriptions and security patches lists more than ten researchers who reported the problems, and Horn is listed on top for both vulnerabilities.

Wolfgang Reinfeldt, Horn’s high school computer-science teacher at the Caecilienschule in the medieval city of Oldenburg about 20 miles from Germany’s north coast, isn’t surprised by his success. “Jann was in my experience always an outstanding mind,” he said. Horn found security problems with the school’s computer network that Reinfeldt admits left him speechless.

As a teenager he excelled at mathematics and physics. To reach the Merkel reception in 2013, he and a school friend conceived a way to control the movement of a double pendulum, a well-known mathematical conundrum. The two wrote software that used sensors to predict the movement, then used magnets to correct any unexpected or undesired movement. The key was to make order out of chaos. The pair placed fifth in the competition that took them to Berlin, but it was an early indicator of Horn’s ability.

Mario Heiderich, founder of Berlin-based cybersecurity consultancy Cure53, first noticed Horn in mid-2014. Not yet 20, Horn had posted intriguing tweets on a way to bypass a key security feature designed to prevent malicious code from infecting a user’s computer. Cure53 had been working on similar methods, so Heiderich shot Horn a message, and before long they were discussing whether Horn would like to join Cure53’s small team.

Heiderich soon discovered that Horn was still an undergraduate at the Ruhr University Bochum, where Heiderich was doing post-doctoral research. Ultimately, he became Horn’s undergraduate thesis supervisor, and Horn signed on at Cure53 as a contractor.

Cybersecurity specialist Bryant Zadegan and Ryan Lester, head of secure messaging startup Cyph, submitted a patent application alongside Horn in 2016. Zadegan had asked Horn, through Cure53, to audit Cyph’s service to check for hacking vulnerabilities. His findings ended up as part of the patent and proved so significant that Zadegan felt Horn more than merited credit as one of the inventors. The tool they built would ensure that, even if Cyph’s main servers were hacked, individual user data were not exposed.

“Jann’s skill set is that he would find an interesting response, some interesting pattern in how the computer works, and he’s just like ‘There’s something weird going on’ and he will dig,” Zadegan said. “That’s the magic of his brain. If something just seems a little bit amiss, he will dig further and find how something works. It’s like finding the glitch in the Matrix.”

Before long, Cure53’s penetration testers were talking about what they called "the Jann effect" -- the young hacker consistently came up with extremely creative attacks. Meltdown and Spectre are just two examples of Horn’s brilliance, according to Heiderich. "He’s not a one-hit wonder. This is what he does."

After two years at Cure53 and completing his undergraduate program, Horn was recruited by Google to work on Project Zero. It was a bittersweet day for Heiderich when Horn asked him to write a recommendation letter for the job. "Google was his dream, and we didn’t try to prevent him from going there," he said. "But it was painful to let him go."

Horn is now a star, at least in cybersecurity circles. He received resounding applause from fellow researchers when he presented his Spectre and Meltdown findings to a packed auditorium at a conference in Zurich on Jan. 11, a week after the attacks became public.

With bowl-cut brown hair, light skin and a thin build, Horn walked his fellow researchers through the theoretical attacks in English with a German accent. He gave little away that wasn’t already known. Horn told the crowd that after informing Intel, he had no contact with the company for months until the chipmaker called him in early December to say other security researchers had also reported the same vulnerabilities. Aaron Stein, a Google spokesman, has a different account though: "Jann and Project Zero were in touch with Intel regularly after Jann reported the issue."

When a fellow researcher asked him about another possible aspect of processor design that might be vulnerable to attack, Horn said, with a brief-but-telling smile: "I’ve been wondering about it but I have not looked into it."

Saturday, January 13, 2018

6 Problems Landlords Face Renting to Section 8 Tenants

By Erin Eberlin

February 26, 2017

There are certain unique challenges a landlord could face when renting to a tenant with a Section 8 voucher. These problems are deal breakers for some landlords, while other landlords feel the advantages of renting to a Section 8 tenant far outweigh the disadvantages. Here are six negatives for you to consider.

6 Potential Problems Section 8 Tenants Create:

1. Frequent Section 8 Property Inspections

2. Do Not Receive Rent Until After Tenant Moves In

3. Section 8 Does Not Pay Security Deposits

4. Wear and Tear Concerns/Possible Property Damage

5. Non-Section 8 Tenants May Not Want to Live in Building

6. Maximum Amount Section 8 Will Pay

1. Frequent Section 8 Inspections

One major issue many landlords have with the Section 8 program is how often they inspect your rental property. These inspections are performed by your local Public Housing Authority. A Section 8 inspector will come to your property once a year to carry out the inspection. Even if there has been no tenant turnover, this inspection has to be done..

The inspector is making sure your unit meets HUD’s Housing Quality Standards. There are 13 areas the inspector will look at to determine if the unit meets HUD’s safety and health standards. These areas include sanitary system, lead-based paint, water supply, electrical and smoke detectors.

Each of the 13 areas must meet certain requirements. For example, the “sanitary facility” must be located in a private area of the home and must only be for the use of the occupants of the home.

It is not uncommon to fail a Section 8 inspection. An example of a hazard that could cause you to fail a Section 8 inspection would be a hot water leak in the bathroom.

This leak could cause potential burns to the tenant.

If you do fail the inspection, you will be given a list of items that need to be fixed. Once you fix all items on the list, you can schedule a re-inspection with the Section 8 office. They will once again send the inspector to determine if all issues have been fixed.

2. Receive Rent After Tenant Move In

Another problem with Section 8 is when you will receive your first rental payment. Typically, you will not be paid by the Section 8 office until after the tenant moves into the property. Due to administrative backups, there have been cases where landlords have had to wait as many as three or four months to receive payment from Section 8. Once you receive the first payment, however, you should expect consistent payment each month.

The delay in payment is something to keep in mind when considering renting to Section 8 tenants. If you do not have the financial ability to be able to wait a couple of months to receive rent, then Section 8 may not be the right choice for you.

3. Section 8 Does Not Pay Security Deposits

Section 8 provides housing vouchers that pay the tenant’s monthly rent. These vouchers do not include an amount for the security deposit.

If a landlord wishes to collect a security deposit, he or she has to get this deposit directly from the tenant. This could be an issue as the tenant has already shown to have income problems by being approved for a Section 8 voucher in the first place.

If they are not able to pay on their own, Section 8 tenants are often able to appeal to other agencies that will provide them with the money for the security deposit. As with any other tenant, you should never allow a Section 8 tenant to move in without first collecting a security deposit from them. The maximum amount you can collect is determined by your state security deposit limit.

4. Wear and Tear Concerns/Property Damage

Another disadvantage of renting to a Section 8 tenant is the belief that Section 8 tenants are very destructive. There have been horror stories about floors being destroyed, cabinets being pulled off the walls, toilets being cracked, garbage and filth everywhere and many more people living in the unit than are listed on the lease.

Certainly, this can happen. However, these problems can happen with any tenant you rent to.

There are good Section 8 tenants and there are bad Section 8 tenants. This is why it is so important to screen all tenants, including Section 8 tenants, properly.

5. May Discourage Non-Section 8 Tenants From Living in the Building

Tenants who do not collect rental assistance may be turned off by the fact that you allow Section 8 tenants in your property. They may believe that you are a “slumlord,” that the property will be dirty or that the tenants will be disrespectful and noisy.

In these situations, the only thing you can do is make sure you place quality tenants in your property and that you keep up with property maintenance. If non-Section 8 tenants see that your property is quiet and in pristine condition, they may change their beliefs about Section 8.

6. Maximum Amount Section 8 Will Pay

The final disadvantage of renting to Section 8 tenants is that there is a maximum amount that Section 8 will pay. Each year, HUD puts together a list of Fair Market Rents for over 2,500 areas of the country. The amount that you will receive from Section 8 will be calculated using the Fair Market Rent for your area for the number of bedrooms you are renting out, such as a one bedroom or a two bedroom.

The amount of the housing voucher will be between 90 percent and 110 percent of the Fair Market Rent. Depending on the condition of your property and the Fair Market Rent HUD has calculated for your area, you may be able to rent your property for a higher amount to a non-Section 8 tenant.

Sunday, January 07, 2018

Healthy Tuna Stuffed Avocado

Wednesday, January 03, 2018

MiFID 2 FAQ

Bloomberg, 1-Jan-18

By Sarah Jones, Will Hadfield and Silla Brush

Everyone in European finance has been abuzz over an obscure acronym -- MiFID II -- that’s about to radically change how assets from stocks to commodities are traded and investors’ money is managed.

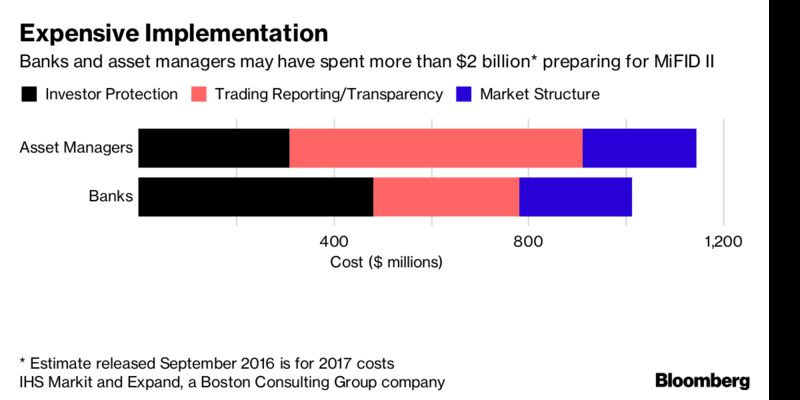

Banks and asset managers across the European Union have spent more than $2 billion preparing for it. Regulators say it will protect investors, boost transparency and rebuild trust that was tarnished by the 2008 global crash. The industry has even spent months finding ways to sidestep parts of it.

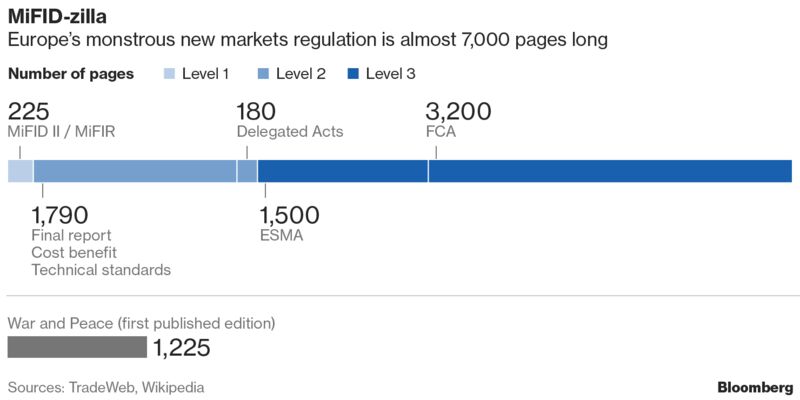

But you’d be forgiven for not paying attention: MiFID II is a law entering into force on Jan. 3 that, according to one count, is already close to 7,000 pages in length with all its addendums. That’s five times longer than Tolstoy’s War and Peace -- and vastly less readable.

It has taken seven years to get the second iteration of the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive into shape because of its wide scope. For starters, it alters how investment research is paid for, how trades are documented and executed, and how brokers share information, find the best prices and pay one another.

“It’s all about casting light in areas of the market that were previously dark, transparency and ultimately treating the investor at all times in a fair manner,” said Ronan Brennan, Dublin-based chief product officer at Compliance Solutions Strategies, which is working with firms to help them meet MiFID’s many demands.

Here’s a look at what MiFID II will mean for European finance.

1) What’s all the fuss about changes to research?

Fund managers now have to pay for the research they use. They can no longer call up their favorite analyst for free for the lowdown on what stocks are hot or how the latest twist in Brexit negotiations will affect their portfolios. They may not even be able to access the hundreds of research reports that have long inundated their email inboxes daily unless they intend to pay.

That’s because MiFID II forces investment banks to charge separately for research and brokerage services to avoid conflicts of interest. Up to now, the cost of research was built into the fees that the likes of Goldman Sachs or Morgan Stanley get paid to execute trades. That worried regulators because it opened the way for commissions to go to banks that offered the best tips and access, rather than the best prices for putting through a client’s trades.

As fund managers get more choosy, it’s widely expected the prices being quoted for access to research will drop in 2018, and some analysts could lose their jobs.

2) How will MiFID make stock markets more transparent?

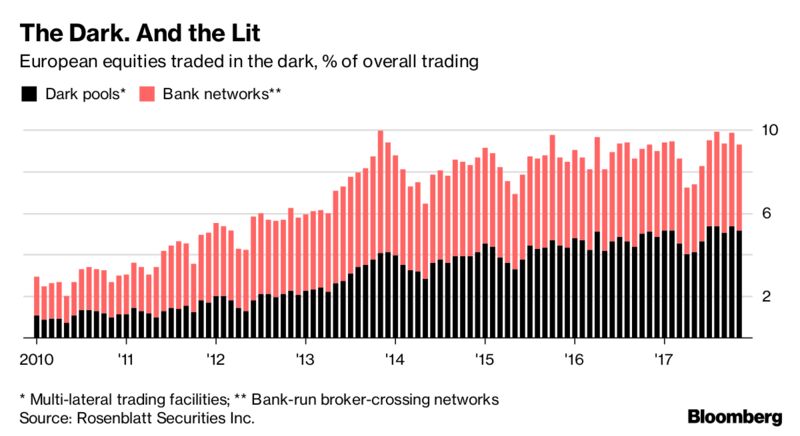

MiFID II clamps down on so-called dark pools. Unlike public, or “lit” markets, such as the London Stock Exchange, dark pools are private markets that allow investors to buy and sell large blocks of shares without revealing beforehand the size of the orders or the price they paid.

Even regulators acknowledge that they serve an important market function. Say a fund manager were to take a huge order for a stock, like two million shares, to a public exchange. On seeing the order, high-frequency traders, who use algorithms to spot block orders, could trade against them almost instantly.

But stock exchanges have complained for years that too much trading takes place on dark pools, depriving investors of the best prices and them of juicy trading fees. So MiFID II imposes limits: only 8 percent of volume in any stock can change hands this way.

3) Will the industry keep trading in the dark anyway?

The short answer: yes. There are two key ways trading will still take place beyond the public gaze for orders that are too small for dark pools but too big to risk placing on a stock exchange:

- The most contentious is called a systematic internalizer. It’s the new name that banks and trading firms will go by when they fill their clients’ buy or sell orders directly using their own capital.

- Public exchanges and some other trading venues will also hold periodic auctions which hide the order size for a stock until sufficient volume has been accumulated to trigger a sale.

"We are likely to see a distinct drop in dark trading once the caps are in force," said Anish Puaar, European market structure analyst at Rosenblatt Securities. "Ultimately most of the trading will move to periodic auctions and eventually systematic internalizers. Some volume may shift to the SIs on day one, but many buy-side firms are still getting to grips with how they work."

4) How does MiFID II subject traders to greater surveillance?

Regulators want to be able to spot risks early and quickly reconstruct events when something suspicious happens, so MiFID II will force the investment community to keep tabs of almost everything. Here’s a sampling:

- Institutions must report information about most trades immediately, including price and volume

- Traders of European Union securities must hand over personal identification, such as passport numbers, to every venue they trade on

- Brokers need to synchronize their clocks and time-stamp all trades

- Bond traders -- for the first time -- need to tell the market about deals they’ve done within 15 minutes of them taking place

- Brokers and investment managers will have to record all conversations related to a deal and store them for at least five years.

5) What’s in store for Jan. 3 -- and 2018?

Implementing the technology needed to comply with MiFID II has some in the industry likening Jan. 3 to Jan. 1, 2000 -- or Y2K -- when many feared the transition into the new century would create havoc on computer systems around the world.

Whether there are IT malfunctions or not, trading volumes are projected to drop across Europe in January as everyone adjusts to the new MiFID world. Given the enormity of the changes, regulators aren’t likely to slap fines on companies for failing to be in full compliance, at least not at first.

Tuesday, January 02, 2018

18 Questions for 2018

Market

1. Will Equity volatility rise?

2. Will yield on US 10Y Treasury break above its range (1.50%-2.40%)?

3. Will we see wage growth in the US?

4. Will US$ index break below its key support, 91?

5. Will crude crude oil reverse its 2H17 gains?

7. Will natural gas bear market end?

7. Will rally in gold continue and price exceed $1,400?

8. Will Financials lead lead the equity market?

9. Will China growth slow down significantly, below 6%?

10. Will Bitcoin craze fade away?

Geopolitics

11. Will President Trump fire Mueller?

12. Will Democrats take over both the House and the Senate?

13. Will North Korean tension escalate?

14. Will Iran-Saudi cold war turn hot and/or Will there be a 3rd Israel-Hezbollah war?

15. Will Russian intervention in Ukraine increase?

16. Will China raise stake in the South China Sea?

17. Will Italian election on March 4 regenerate existential crisis for the Euro Area?

18. Will UK successfully navigate Brexit negotiation?

1. Will Equity volatility rise?

2. Will yield on US 10Y Treasury break above its range (1.50%-2.40%)?

3. Will we see wage growth in the US?

4. Will US$ index break below its key support, 91?

5. Will crude crude oil reverse its 2H17 gains?

7. Will natural gas bear market end?

7. Will rally in gold continue and price exceed $1,400?

8. Will Financials lead lead the equity market?

9. Will China growth slow down significantly, below 6%?

10. Will Bitcoin craze fade away?

Geopolitics

11. Will President Trump fire Mueller?

12. Will Democrats take over both the House and the Senate?

13. Will North Korean tension escalate?

14. Will Iran-Saudi cold war turn hot and/or Will there be a 3rd Israel-Hezbollah war?

15. Will Russian intervention in Ukraine increase?

16. Will China raise stake in the South China Sea?

17. Will Italian election on March 4 regenerate existential crisis for the Euro Area?

18. Will UK successfully navigate Brexit negotiation?

Monday, January 01, 2018

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)